New framework programme

Europe’s hour of innovation has come. Perhaps.

Gabi Lombardi, Director of the European Alliance for Social Sciences and Humanities, fears that Europe’s standard of living is in danger.

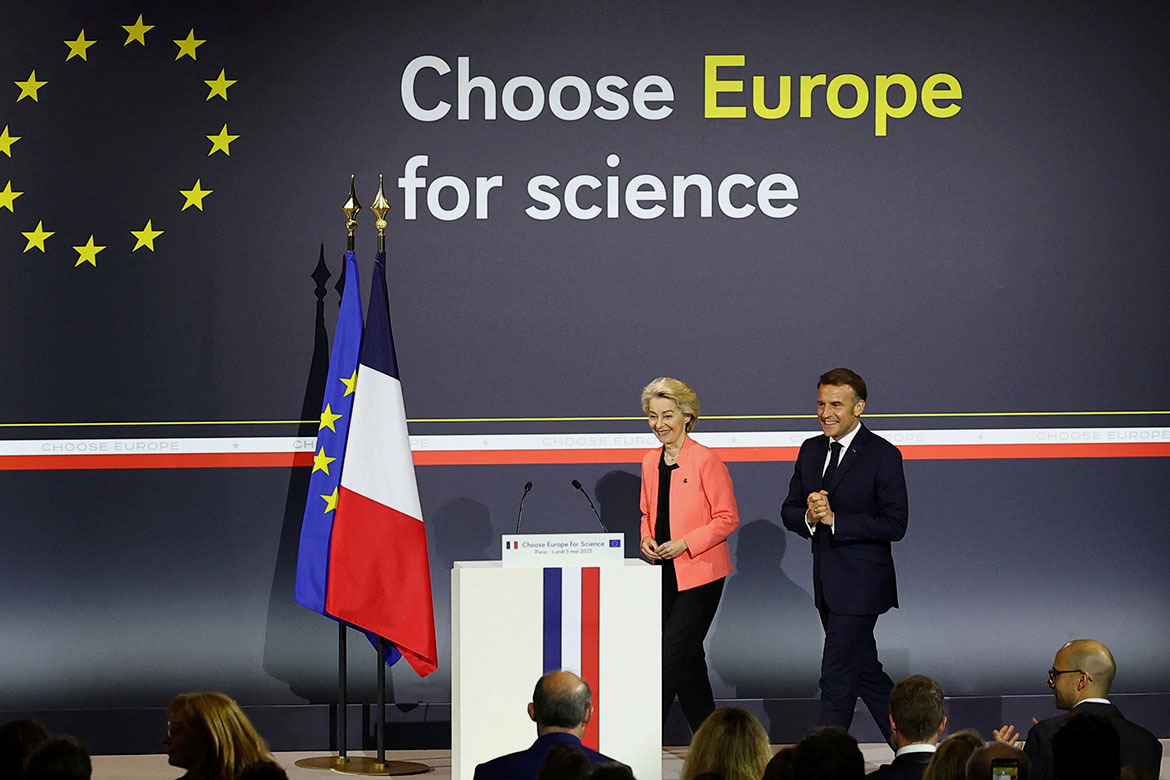

Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, strides to the lectern with French President Emanuel Macron to announce the initiative ‘Choose Europe for Science’. | Photo: Gonzalo Fuentes / AP / Keystone

“We must make Europe the best place in the world to pursue science”, said Ursula von der Leyen, the President of the European Commission, in a speech about the EU’s 10th Research Framework Programme (FP10), which will commence in 2028. “Not only for fundamental research”, she continued, “but through the entire life cycle of innovation, from the university laboratory to world-leading unicorns”.

According to the magazine Science Business, she also stated clearly that the “current budget was designed for a world which no longer exists … [the] budget of tomorrow will need to respond fast”. Christian Ehler of the European People’s Party is of a similar opinion: “What we have learned in an ever-faster innovation setting globally is that we are too slow and over-descriptive”.

Whereas both von der Leyen and Ehler are keen to increase the pace of progress and to make collaborations with industry easier to set up, Gabi Lombardo, the Director of the European Alliance for Social Sciences and Humanities, takes a somewhat different stance. “Europe today enjoys some of the highest living standards in the world. That success was not automatic. It was built on decades of deliberate investment in public goods such as healthcare, education, social protections, cultural infrastructure and academic freedom”. But there’s a problem. “That legacy is now being tested”, she said to Science Business.

“As budgets tighten and political rhetoric hardens, the role of the humanities and social sciences in shaping our collective future is at risk. And that’s a mistake we can’t afford”. The priorities of FP 10 – competitiveness, defence and democracy – are the right ones, she says, but we’re approaching them in the wrong way.

The real problem is “limited technology transfer”. And she concludes by saying that “without understanding the human, cultural and institutional barriers to adoption, innovation cannot deliver its full benefits”.