Fairness versus egotism – Europe’s ambivalence towards asylum

When it comes to an allocation formula for asylum seekers, Europeans are fair, but with certain caveats. And they don’t want any Muslims.

Refugees arriving on the Greek island of Lesbos in the autumn of 2015. | Image: shutterstock/Nicolas Economou

Europe’s asylum policy offers more space for fair solutions than you might think. This is the conclusion of Dominik Hangartner, a professor of political analysis at ETH Zurich and the London School of Economics. He is a co-author of a study in which 18,000 Europeans from 15 countries offered their opinions on two topics. First: What type of asylum seekers would they welcome? And secondly: How should they be allocated between countries? Their answers demonstrate a mixture of self-interest and selfless solidarity. “People prefer young, well-educated people”, says Dominik Hangartner. In other words, those who can make a contribution and won’t be a burden on the social system. But humanitarian reasons also play a role. Asylum seekers are more likely to be accepted if they are disabled or have been tortured or traumatised, or have lost their families. This is more or less in line with current international laws on refugees – and quite in contrast to a third result from the survey: Muslims are less welcome than Christians.

The better educated are more welcome

Surprisingly, this pattern can be observed across all social groups and in all countries, with just a few discrepancies. For example, those who are politically on the left are also sceptical about Muslims, just less so than those on the right. The people surveyed in Poland, Czechia and Greece are especially Islamophobic, while in German-speaking countries people are more sceptical than in the rest of Europe about those from Kosovo. In one matter, Switzerland is an unusual case. Those surveyed here also prefer those who already had work in their homeland, but in contrast to other countries, it plays no role here what kind of career they had – whether doctor, teacher, cleaner or farmer, they’re all equally welcome. Otherwise, there’s a hierarchy everywhere. The more well-educated someone is, the better. Hangartner surmises that it could be because a professional training enjoys a relatively high status here.

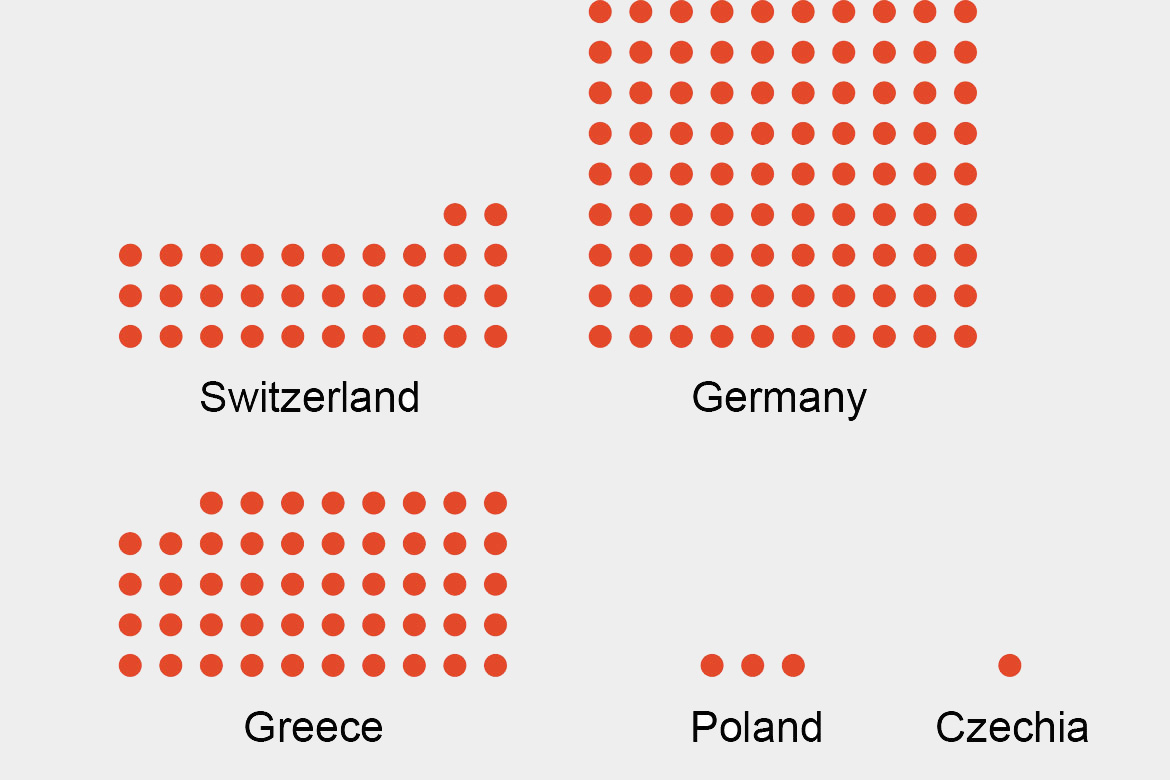

The number of asylum seekers per 10,000 inhabitants in 2016. If an allocation formula were applied to them according to the size and economic strength of countries, Czechia would have to take more, while Germany would take fewer.

When it came to the allocation formula, those surveyed could choose between three models: the status quo, the same number for every country, or an allocation according to the size and economic strength of the different countries. The last solution was the most popular everywhere. On average, 72 percent of people were in favour of it. “This principle is intuitively comprehensible and fair”, explains Hangartner. “The idea that those should do more who can do more is a very powerful norm”. These noble principles soon come under pressure, however. In all ten countries that would then have to take on more refugees than hitherto, the degree of approval of this system sinks noticeably.

Fairness trumps egotism

Czechia, for example, which has taken on the fewest asylum seekers of all European countries, would have to take almost 25 times more of them. Once people realise this, the degree of acceptance of such an allocation formula plummets, and three quarters of those surveyed would prefer the status quo. It’s very different in Germany. No other European country has taken in so many refugees in recent years, in either relative or absolute terms. So Germany would be massively relieved by a proportional allocation formula. Nevertheless, the basic acceptance of such a system was initially below average (58 percent), but rose by 10 percent when people realised what its consequences would be.

Switzerland is one of the three countries that are most clearly in favour of a ‘fair’ allocation. Almost 80 percent of those surveyed would be in agreement with it. But this percentage sinks by more than 20 percent when people realise that Switzerland would have to take in some 2,000 more asylum seekers on top of the 37,000 who are already here. “In all countries, we can observe two basic drivers: egotism and fairness”, says Hangartner. What was new to him, and what also surprised him, was how important fairness is to the voting population of Europe. A majority of 55 percent would support the proportional formula, even when they know what the consequences would be.

Andreas Minder is a freelance journalist in Zurich.