INTEGRATION

More Swiss than the Swiss

A study shows that, in German-speaking Switzerland, expectations regarding integration are higher for ‘foreigners’ than for the rest of the population.

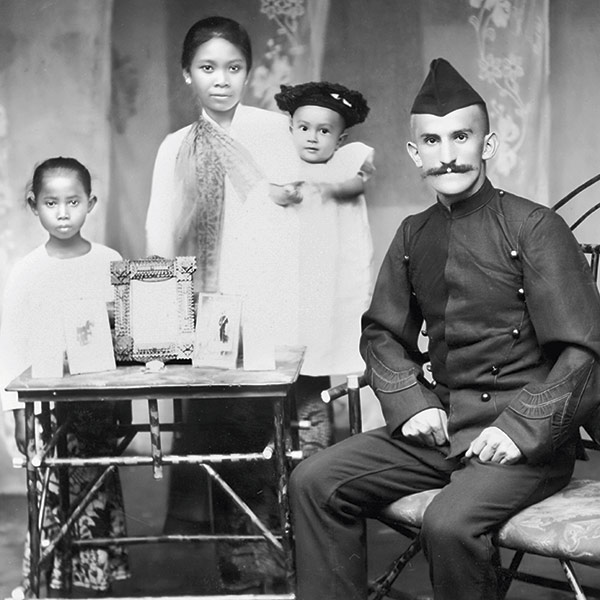

More Swiss than the Swiss: It seems that those regarded otherwise as ‘foreigners’ are expected to do more when it comes to civic engagement and upholding the principles of the constitution. | Photo: Sabina Bobst / Keystone

When it comes to integration, do we demand more from those seen as ‘foreigners’ than from society in general? Stefan Manser-Egli and Philipp Lutz of the SNSF National Centre of Competence in Research ‘NCCR On the Move’ set out to measure it. Their study reveals a ‘migration bias’ in German-speaking Switzerland that is absent in French-speaking Switzerland.

A thousand subjects, randomly divided into two groups, were questioned about twelve social norms. The first group evaluated how important these norms were regarded for ‘people in general’. The second group assessed how important they are when it comes to those regarded as ‘foreigners’. This term was specifically chosen due to how it currently dominates public discourse.

It appears that in German-speaking Switzerland, expectations of foreigners are particularly intense when it comes to local civic engagement and respect for constitutional values, whereas these behaviours are considered less important for society in general. This migration bias remains moderate – a few percentage points – but is statistically significant.

In French-speaking Switzerland, the bias disappears. There the test subjects formulated higher expectations for society overall than specifically for foreigners on aspects such as religious practice, work and gender equality. This regional difference can be explained by the historical context. German-speaking Switzerland tends towards an assimilationist conception of citizenship, whereas French-speaking Switzerland has a more multicultural approach.

The originality of this research lies in its method. Qualitative research already argues that the discourse on integration systematically targets foreigners while exempting the majority of citizens from the same requirements. But this hypothesis had never been tested by an empirical quantitative study until now.

“We would like to reproduce this experiment in the Netherlands, where there is also a powerful integrationist discourse, to test whether the migration bias observed in Switzerland can be seen outside Swiss settings”, says Manser-Egli, currently a postdoc at the University of Amsterdam. For him, this research poses the following question: “If the concept of integration can generate double standards, shouldn’t we favour universal standards applicable to everyone?”