Textile manufacturers in the 18th century profited from a worldwide network

The members of the Old Swiss Confederacy in the 18th century – from Geneva to Glarus – were leaders in the manufacture of printed cotton textiles known as ‘indiennes’.

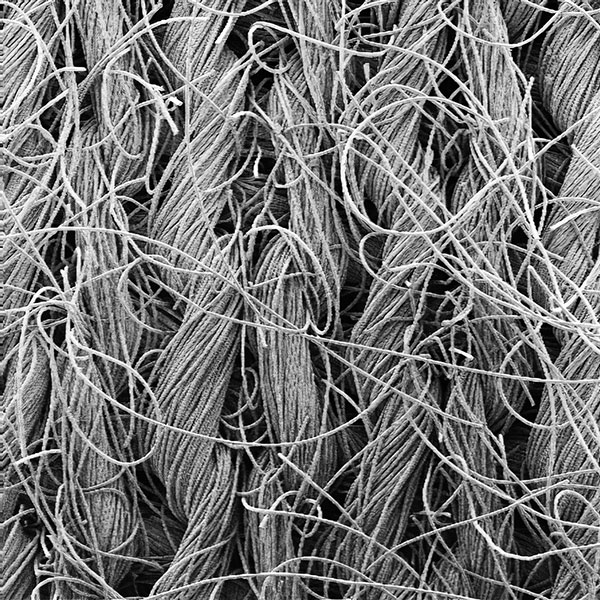

An indienne with exotic flowers and foliage. This printed cotton conquered the world in the 18th century. | Image: St. Gallen Textile Museum, Inventory No. 25533

Cottons printed with brightly coloured patterns were unusual, even fascinating to people in early modern Europe. Once the sea route to India was discovered, there was an increase in the trade of exotic goods. From the 16th century onwards, the Dutch, Portuguese and English imported Indian cotton textiles to Europe. They were a low-maintenance alternative to the linen and woollen garments that were the norm back then, and were much more pleasant to wear. With their artful, flowery designs, these cotton textiles – known as ‘indiennes’ or ‘chintz’ – were also as attractive as the silks worn by the upper classes, but considerably cheaper. It was hardly surprising that interest in cotton also grew in the Swiss cantons of the time, among both consumers and businessmen. But potential manufacturers had a problem – they first had to learn the age-old skills of printing and dying that were practised by Indian artisans.

In this they were successful, as research has already proven. The Swiss indiennes industry experienced its heyday in the 18th century. The boom began in the 1690s in Geneva, when Huguenot refugees from France set up the first indienne manufacturing companies. Local entrepreneurs followed their example. This ‘calico printing’ spread via Neuchâtel, Biel and Basel to Aargau, Zurich and Glarus. But the story of indienne production in Switzerland has up to now been treated largely as a national phenomenon, says Kim Siebenhüner, a historian at the Friedrich Schiller University in Jena. She’s now expanding the picture to offer a global, historical perspective.

Support instead of prohibition

Siebenhüner’s research was undertaken at the University of Bern where she was an SNSF professor. She and her team demonstrated that the success of the indienne industry came about thanks to a transfer of knowledge and technology between India and Europe, from which Swiss manufacturers also profited. “But there was more than that”, says Siebenhüner. “The Swiss were themselves active players in consolidating the global communication of knowledge and goods in the 18th century”. Switzerland’s contribution to this early process of globalisation has received little attention up to now. But how did it come about that a small, landlocked country became a hub of the indienne industry, despite having neither direct access to any of the big sea ports nor any colonies, let alone any ‘East India Company’ of its own?

Siebenhüner and her colleagues investigated many different sources, including the extant company correspondence of the indienne manufacturer Laué & Cie. in Wildegg in today’s canton of Aargau. They also found relevant information in old inventories of the city of Bern and from examining indienne objects in museums. The Swiss indienne manufacturers were aided by the political environment. France, England and Prussia tried variously to protect their own weavers from the influx of Asian cottons by placing bans on their import and manufacture. But Switzerland was very different, because the local authorities supported this new economic sector by offering cheap loans or privileges to help buy a water mill, for example. “Indienne production was regarded as a welcome source of new jobs that brought people into paid employment”, says Siebenhüner.

No fear of revolution

In social terms, too, Switzerland had a lot less to fear from potential internal conflict. Whereas people warned of a possible overthrow of the existing hierarchies in England if middle-class, bourgeois households were able to afford bed covers, clothes and jackets made of indiennes, this moralising discourse was quite unknown in Switzerland. Was this perhaps because the consumer boom triggered by the indiennes was more moderate here than in the rest of Europe? The historian John Jordan seems to think so, based on his own research findings. He has studied so-called ‘Geltstagssrödeln’ in Bern – inventories that were drawn up in cases of private bankruptcy – and concluded that “in 18th century Bern, cotton was simply one more type of textile alongside wool and linen”.

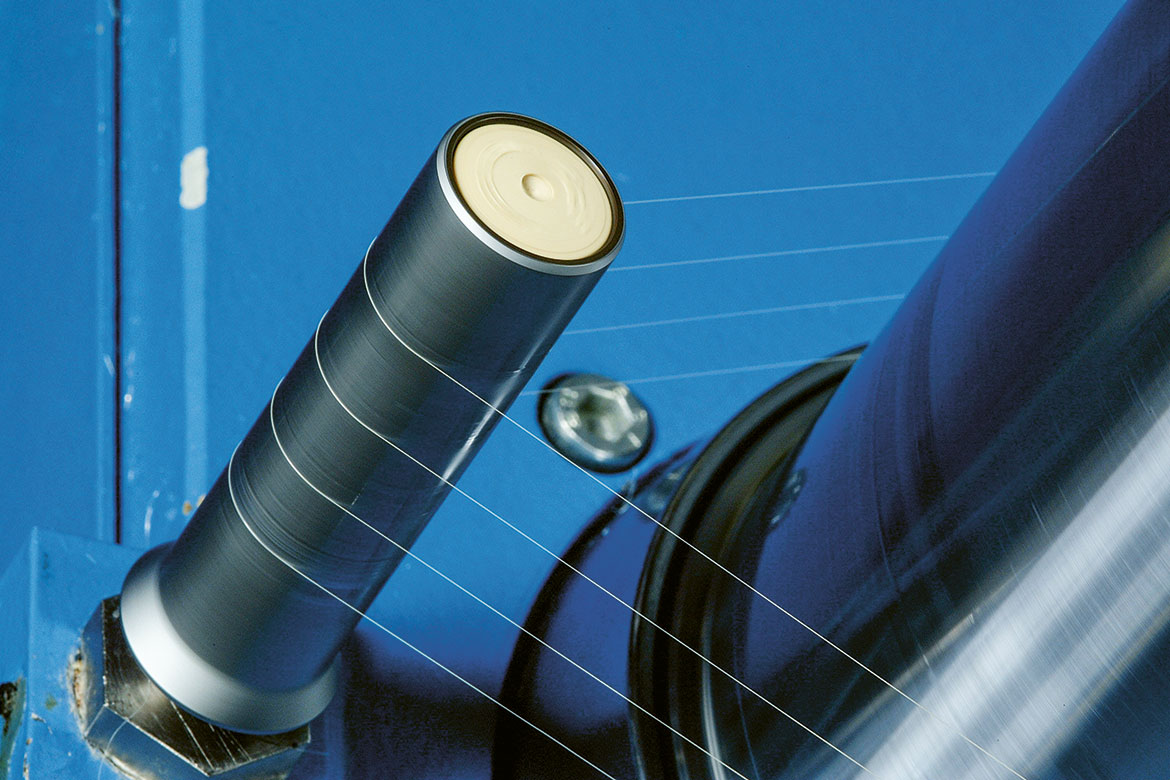

Indienne manufacture is regarded as a precursor of industrialisation in Switzerland because it brought together different trades under the same roof for the first-ever time: pattern designers, engravers of wooden forms, colourists and assistants, as well as managers. But production was not yet mechanised, and was extremely cumbersome. “The Swiss acquired the necessary practical knowledge by procuring skilled workers from abroad”, says Kim Siebenhüner. The expertise of Armenian specialist workers was in particular demand. They came from Asia under their own steam and set up pioneering indienne workshops in Marseille, Geneva, Livorno and Amsterdam.

A century of learning

Soon it was the artisans trained in Swiss workshops who were taking their knowledge of indiennes elsewhere, and who became sought-after at home and abroad. According to Siebenhüner, the Swiss further refined the technology and the styles of indiennes: “They varied the raw materials and designed patterns with more familiar subjects”. It was “a century of learning”. Siebenhüner speaks of a “mimetic, imitative economy in the 18th century”, in which the mobility of experts and the circulation of knowledge served to stimulate the Swiss economy. The Swiss put a greater emphasis on utilising their knowledge, and were less afraid of the possible damage that might arise from industrial espionage. Unlike their colleagues abroad, Swiss textile producers didn’t spend much time lobbying to attain legal protection for their designs and techniques. It was only in the 19th century that the Swiss set up their own patent law.

Much of Switzerland’s indienne production was intended for export. Manufacturers like Laué sent their commercial agents with sample books to the European trading centres in order to procure contracts and to ensure that they kept in touch with the taste of their clientele. Thanks to their presence across Europe, from Naples to Copenhagen, Bordeaux and Leipzig, the Swiss managed to procure outlet markets in Asia, America and Africa for their locally produced indiennes, as the Bernese historian Gabi Schopf has established: “They played an active role in creating a worldwide trade in textiles, and ensured that Switzerland participated in early-modern globalisation”. This commercial success naturally also had its darker side: Swiss indiennes also served as exchange goods in the international slave trade. The indiennes are an astonishingly diverse topic – they were a textile that changed the economy and society. In the light of today’s controversies about the free movement of people and the pros and cons of economic isolation versus liberalisation, historical research can serve to remind us of the open, global reach of Swiss business long before industrialisation and digitisation.

Exhibition of indiennes in the Swiss National Museum, until 14 October 2018

Susanne Wenger is a freelance journalist who lives in Bern.