Simulating tsunamis can save lives

Tsunamis are a threat to people living both in coastal areas and in valleys downstream from artificial reservoirs. Researchers have been investigating how buildings can best withstand waves that are several metres high.

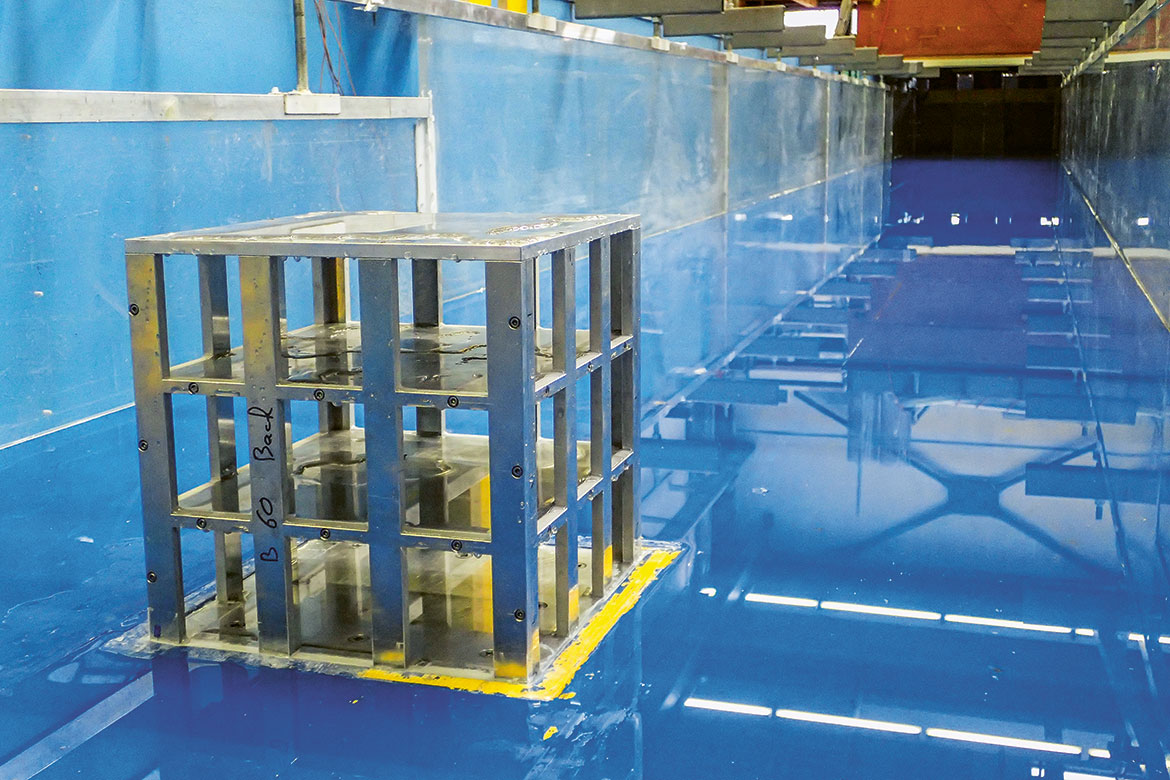

Here comes the flood. But will the building – simulated here by the cube – be able to withstand it? | Image: Davide Wüthrich.

Tsunamis are usually caused by powerful earthquakes in the ocean, but landslides in reservoirs can also trigger them. This is exactly what happened in 1963 in the Vajont Valley (Friuli, Italy), for example, when some 1,900 people died after a giant wave spilled over a 260-metre-high dam wall. The current melting of the glaciers will most likely lead to more landslides into artificial reservoirs.

“There’s not been much scientific investigation into how tsunamis arise, nor into the damage they cause”, explains Davide Wüthrich, a doctoral student at the Hydraulic Constructions Laboratory of EPFL. In order to find out how the architecture of buildings reacts to the destructive power of a tsunami, he has developed a simulator: a 14-metre-long water channel that is linked to a container with seven cubic metres of water. When this water is emptied into a lower-lying catch basin, the water sloshes into the channel and triggers high waves.

In order to simulate different types of building, Wüthrich installed cubes in the channel with openings of varying sizes. These are situated on force plates that measure the impact load when the channel is flooded. “What was surprising was that the impact force of the wave on the cube decreases in almost exact proportion to the surface areas of the openings”. In the real world, this means that the more doors and windows that a building has in vulnerable zones, the more effectively one can lower the force of a wave on that building. There is less of a chance that the buildings will collapse, and so residents fleeing up onto the roof would be safe.

But can one truly simulate real disasters in the lab? The Japanese authorities certainly seem impressed by Wüthrich’s work. They are currently working together with the Hydraulic Constructions Laboratory of EPFL to evaluate one of their own tsunami models.