“There are always going to be quirky studies”

Last year, the project ‘Cheese in surround sound’ went viral. Eight large Emmental cheese wheels had been listening to a type of music for several months, ranging from Mozart to Led Zeppelin. A ninth cheese was the ‘control wheel’. The Bern University of the Arts HKB was involved in it, and Thilo Huehn from the Zurich University of Applied Sciences carried out the closing ‘sensory consensus analysis’. After the results were made public, the headline “Cheese exposed to hip-hop tastes better” blew up. The communication scientist Mike S. Schäfer talks to us about the way projects like this are reported in the press.

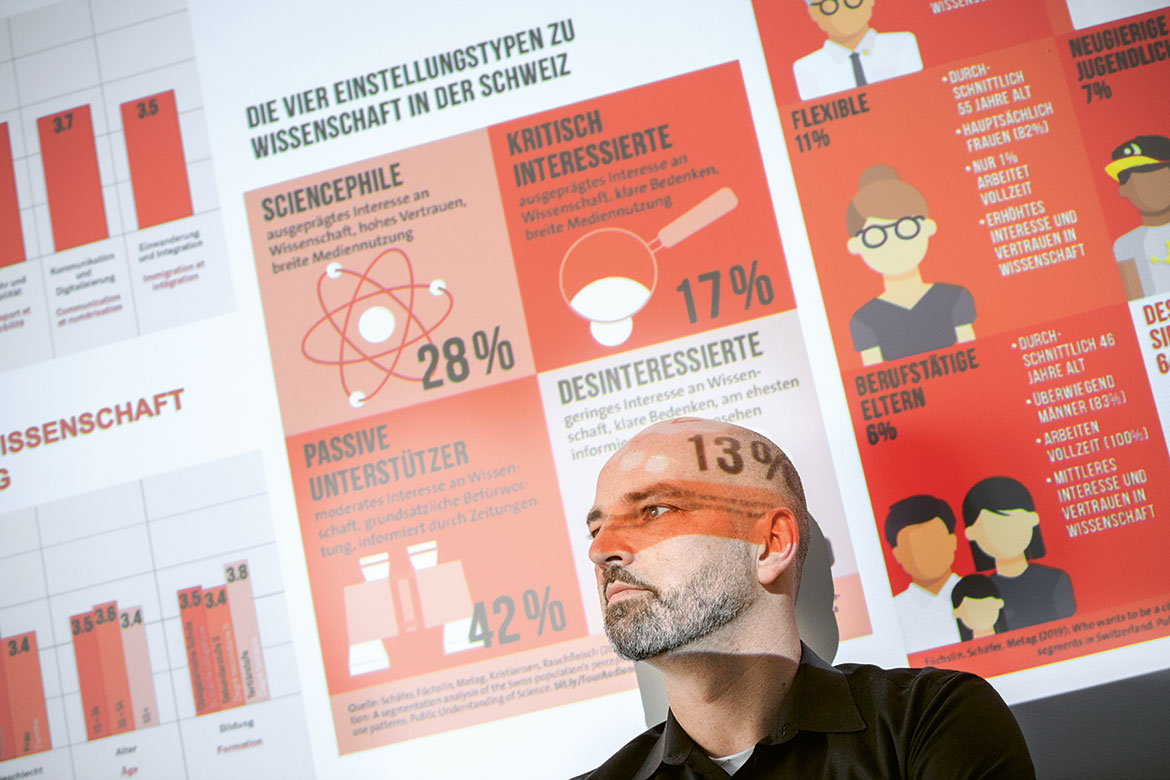

Mike S. Schäfer is currently working on a research project to determine how external communication has changed at Swiss universities in recent decades. | Image: Valérie Chételat

The Director of the Bern University of the Arts Thomas Beck said: “We never expected such an international response in the media”. Were you surprised too, Mike Schäfer?

The quirkiness of the project made it newsworthy. It’s an unusual story, because no one expects music to have an impact on cheese (and in fact, it didn’t, either). Besides, cheese is a national symbol of Switzerland. So the project was ideal for a humorous story in the media. Nevertheless, at any one time there’s always going to be a large number of studies that are somewhat quirky in design. But it’s almost impossible to predict which of them will go viral.

Every university today is also a PR machine. Is this cheese project a sign that the communication strategies of our universities are successful?

The media and PR work undertaken by scholarly institutions has indeed expanded enormously in many countries. They have more staff for this, more resources, and research findings are now given a more professional media gloss.

But that’s just one side of the story.

Sure. There has been an increase in the number of media reports on scientific issues in recent years. But at the same time, the number of active science journalists has decreased. They’ve got less time and work under worse conditions. The resultant conflict doesn’t make for a better quality of reporting. Then we have the increasingly professional PR departments that are now offering ready-made articles. This doesn’t do much to improve the quality of science journalism either. Journalists are always on the lookout for oddities to put on social media, because they bring more clicks. The cheese project ticked all the right boxes.

The cheese project didn’t actually offer any scientific proofs. Outside the high-quality science journals, are the media at all interested in real facts?

The kind of popular channels that made the cheese project go viral are not primarily concerned with scientific quality. But as a rule, the following applies: No individual study ever offers the last word on a topic. It’s only really worth reporting scientific findings when they’ve been demonstrated by a series of studies.

So is it misleading when the media report on individual studies?

We should at least be cautious. You can see that from studies on nutrition. Is a glass of wine a day healthy or not? Such topics garner attention, but they’re rarely the subject of reliable reporting. The non-scientific public then gets the impression that science has nothing definitive to say. But people who are actively engaged in science understand that individual studies can sometimes contradict each other, that dissent is normal, and that science corrects itself.

Horizons also offers news about individual studies.

But Horizons at least has a scientifically educated readership that is better able to contextualise individual studies. For other readerships, however, that kind of reporting is far from ideal.

But if we can’t report on individual studies any more, then less will be written about science in general.

Not necessarily. Even today, most scientific articles don’t actually get published in the science pages of the media, but on the pages meant for politics, business and culture. They’re more about societal issues such as the consequences of climate change or immigration, for which scientists can provide expert information.

Let’s return once more to the cheese project: Should the universities have made it clearer that it was an art project, not a science project?

Research staff at universities enjoy the greatest trust among the general population. And that means you’ve got to act responsibly. Most university communication departments do that. The cheese project was an exception.