Feature: AI, the new research partner

Your co-author, the computer

Combining large language models like GPT with reinforcement learning could lead to AI discovering fundamentally new approaches to research. We take a look into the crystal ball.

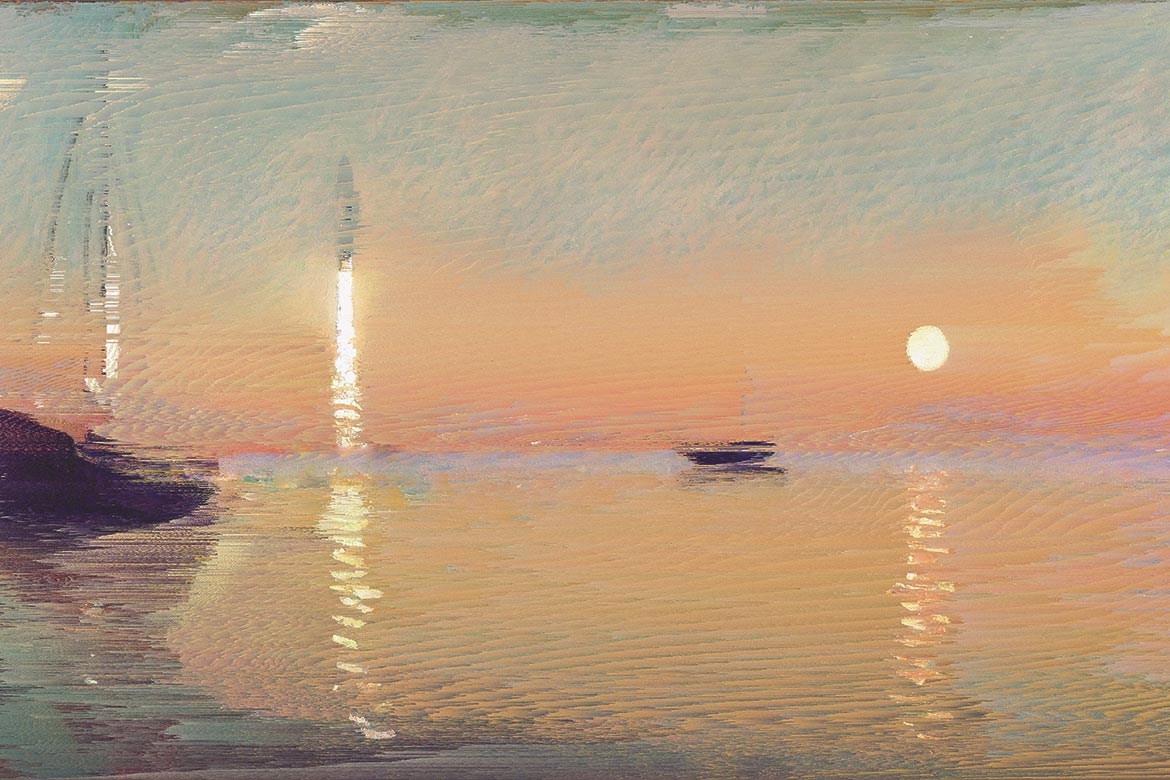

The artist Jonas Wyssen and an AI program have together created a new version of Claude Monet’s famous painting ‘Impression, sunrise’. In Monet’s day, his style unsettled the art world and set new standards for art – just like algorithms are doing today. | Image: Jonas Wyssen

The latest models of artificial intelligence (AI) are causing an upheaval of near-mythological proportions. The use of language generators such as GPT-4 and image generators such as Stable Diffusion has prompted Thomas Friedman, a well-known columnist for the New York Times, to compare our situation today with that of the demigod Prometheus, who in the Ancient Greek myth gave fire to mankind and brought about the birth of civilisation. Friedman believes that this new technology is changing all that we know and do: “You can’t just change one thing, you have to change everything. That is, how you create, how you compete, how you collaborate, how you work, how you learn, how you govern and, yes, how you cheat, commit crimes and fight wars”.

Research doesn’t feature in Friedman’s list. Is this because exploring as yet unmapped landscapes is still the domain of humans? This question has also been bothering the EPFL professor Rüdiger R. Urbanke, who is trying to assess the future potential of AI at the Geneva Science and Diplomacy Anticipator: “If you’d asked me three months ago which jobs are the most likely to be threatened by AI, I would probably have said the exact opposite of what I think today, as I believed that jobs would be safe wherever a certain degree of originality is important. But now, with GPT and Stable Diffusion, you can suddenly imagine the whole creative industry having to cope with competition from an AI that can work pretty competently”.

Pedro Domingo, a professor emeritus at the University of Washington, believes that AI will one day be conducting independent research and will indeed discover new things: “Some say machine learning can find statistical regularities in data, but it will never discover anything deep, like Newton’s laws”, he wrote in 2016 in his successful introduction to AI entitled ‘The Master Algorithm’. “It arguably hasn’t yet, but I bet it will”, he added. This question arose in connection with Big Data, and it prompted the tech writer Chris Anderson to publish a manifesto for a new science in ‘Wired’ magazine: “Correlation supersedes causation, and science can advance even without coherent models, unified theories, or really any mechanistic explanation at all. There’s no reason to cling to our old ways. It’s time to ask: What can science learn from Google?”

AI can fold proteins

Hardly anyone could have guessed the upheavals that we’re undergoing today. AI has meanwhile become an established tool in many fields of academic research without immediately raising any fundamental, epistemological questions. The most recent example is that of AlphaFold, a program that can solve an old problem pretty well in many cases, namely precisely predicting how a protein will fold. This surprising advance has been made possible by the company DeepMind, which had perfected its methods while playing Go. They don’t give their AI any precise instructions on solving the problem, but they optimise it by rewarding progress and punishing setbacks by means of a points system. They use the method of reinforcement learning, which means that the AI is left to decide exactly how it should arrive at a solution. This often leads to an unexpected approach and to unexpected results. At the time, Go specialists compared its achievements to discovering a new continent.

It remains an open question as to whether or not researchers will one day be able to use creative AI to penetrate metaphorically empty areas on the map – regions that no one could possibly anticipate finding. Jack Clarke is an AI evaluation specialist and the author of the influential newsletter ‘Import AI’. He sees parallels between the development of reinforcement learning today and the state of the large language models like GPT just a few years ago. It is possible to recognise a degree of conformity between the size of these models and how well they perform. As soon as it becomes foreseeable that the performance of these systems can be increased decisively by providing additional resources, these developments will accelerate even further.

The ‘next big thing’ could therefore mean linking reinforcement learning with these language models. Perhaps researchers will no longer learn new things by using AI methods, but by conversing directly with an AI. And perhaps the age of methodological research is far from over, despite what Anderson thinks – only it’s an AI that will be reinventing the models, theories and mechanistic explanations, not humans any more.

This vision may sound outlandish. To be sure, it’s true that the large language models ‘only’ calculate the most plausible continuation of any linguistic input. But since the advent of GPT-4 at least, it’s no longer good enough for us simply to brush aside these results and argue that these models only ‘pretend’ to know something, and that they have failed to acquire any appliable knowledge. To illustrate this, we should consider that if we were to ask GPT-3 (the predecessor of GTP-4) to play a game of chess, it would play a nonsensical game with great conviction. The step up that we’ve taken with GPT-4 is more of a giant leap, because this AI has learned the rules of the game, and can play it at a thoroughly respectable level.

No time for a ten-year plan

Urbanke is urging us to expect the unexpected because he is convinced that there will always be surprises waiting for us in the broad field of AI. “You can’t make a ten-year plan, and you have to stay close to developments. This means that you have to do basic research”. Which naturally once more raises the question of resources, if the models are going to become more and more powerful. Will national infrastructures even be able to keep up with the big companies? Urbanke again: “It doesn’t have to be another CERN. A few players working together will suffice”. In any case, he isn’t worried: “We are well positioned in Switzerland”.